Excessive money printing will lead to inflation. We are at risk of a Weimar Republic style hyper-inflationary crisis!

Tightening credit markets put us at risk of deflation. Deflation was the true culprit behind the Great Depression. We are on the brink of another deflationary collapse!

If you’ve spent any time reading economic news and blogs both the above arguments are probably familiar to you. Both arguments seem to have at least some merit. Which is correct? How will the crisis unfold?

Indeed one of the questions I received on my last post, Bondpocalypse, essentially boiled down to: In the battle between inflation due to loose monetary policy and deflation due to tightening credit markets, which wins? Stated differently, if the bondpocalypse occurs and massive debt monetization is unleashed, could the economic slowdown reduce the total money supply such that inflation is held in check or we even get deflation?

I’ve wrestled with these questions continuously over the last several years as I’ve tried to make sense of the craziness that passes as economic policy these days. Here’s my take.

The Deflation Argument Holds Water

The premise of the argument, that economic slowdowns cause deflationary pressure, makes a certain amount of logical sense. After all, recessions and depressions are associated with a tightening of the credit market which, in our fractional reserve system, directly reduces the money supply.

How? Well, in a fractional reserve system only part of the total money supply is controlled by the central bank. On top of this base central bank money, additional money is loaned into existence by the banks. The amount of money the banks loan into existence is bounded by the reserve ratio. This reserve ratio effectively sets a hard upper limit on how much money the banks can loan into existence. But there’s no corresponding lower bound: People can’t be forced to borrow and banks can’t be forced to lend,

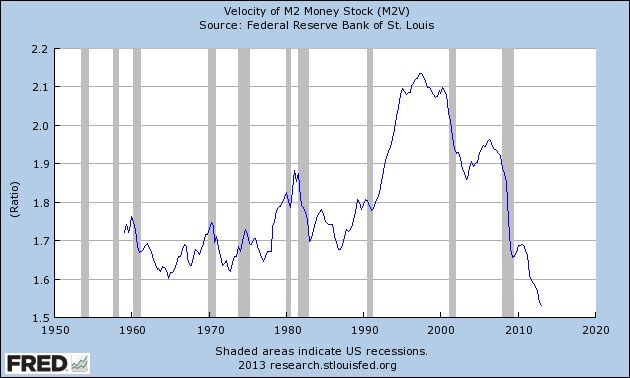

The rate at which money is created in this fraction reserve system can be measured by looking at a metric called the ‘Velocity of Money’. The higher the velocity of money, the more leveraged money the banks are loaning into existence.

Here’s the key: If bank lending slows for any reason, the rate of growth of the total money supply will decrease and the velocity of money will fall. If the total impact of this decrease in the money supply exceeds the new money being injected into the system, deflation results.

Thus looking at the velocity of money gives us a clear indicator of how much deflationary pressure exists on the money supply:

It couldn’t be more obvious: Velocity of money has plunged since the 2008 financial crisis. There has been no recovery either. Instead, in the last couple of years, the velocity of money has decreased to well below historical norms. Banks aren’t lending (or aren’t able to lend).

The conclusion is that there must then be clear deflationary pressures on the economy. I would conclude that the premise of the argument used by the deflationists is valid. Clearly the ongoing economic slowdown is putting extraordinary deflationary pressures on the money supply.

So Where’s the Deflation?

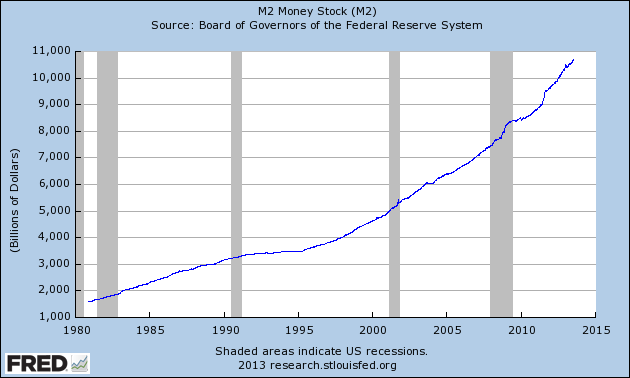

Given the drastic reduction in the velocity of money, one might expect we’d already be experiencing deflation. This is not the case. Here’s what the money supply looks like:

The overall trend is clear – total money supply continues to increase even in the face of a drastic slowdown in the velocity of money.

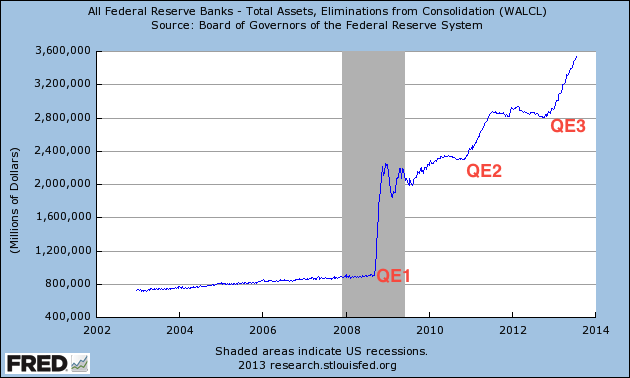

The reason: Quantitative Easing (QE). Since the onset of the economic crisis the Federal Reserve has been pouring money into the economy. Even with a lower velocity, the printing by the Fed has served to keep the system slightly inflationary.

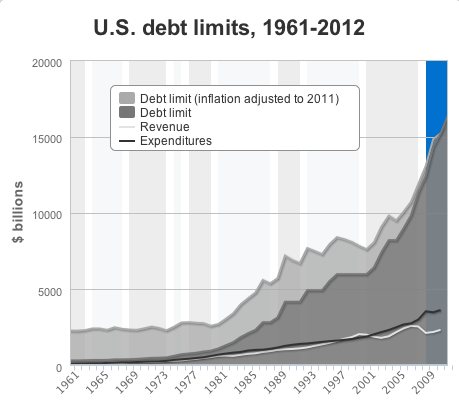

Government Debt

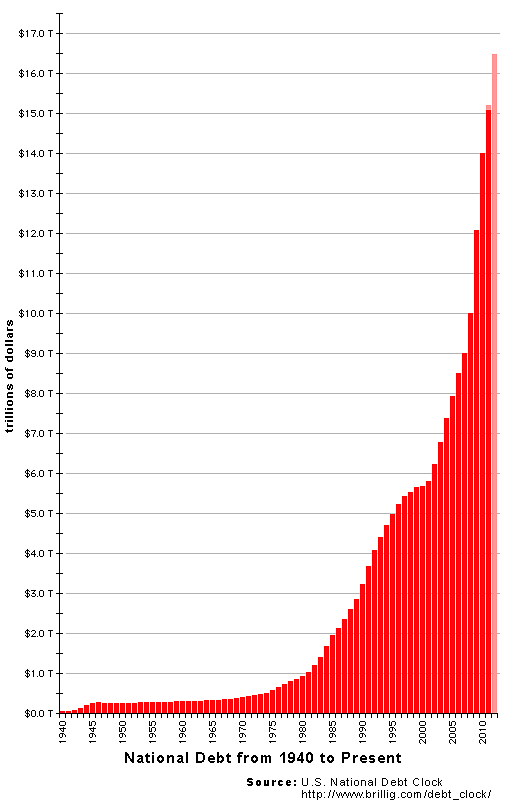

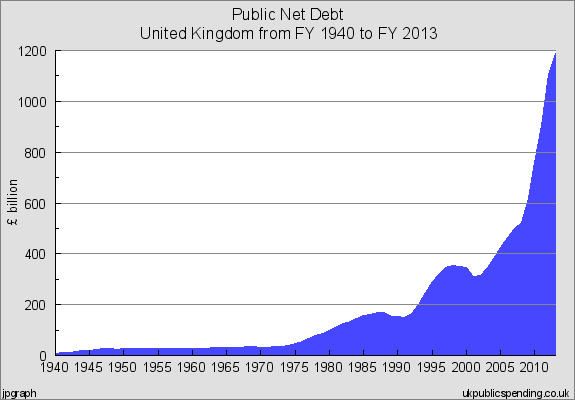

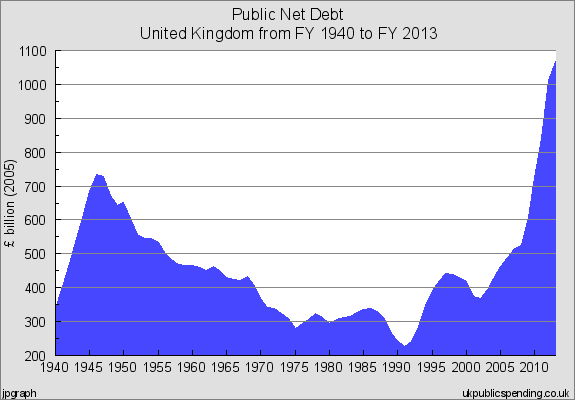

As I covered in my last post, the major use of QE is to allow for the monetization of the exponentially growing government debt:

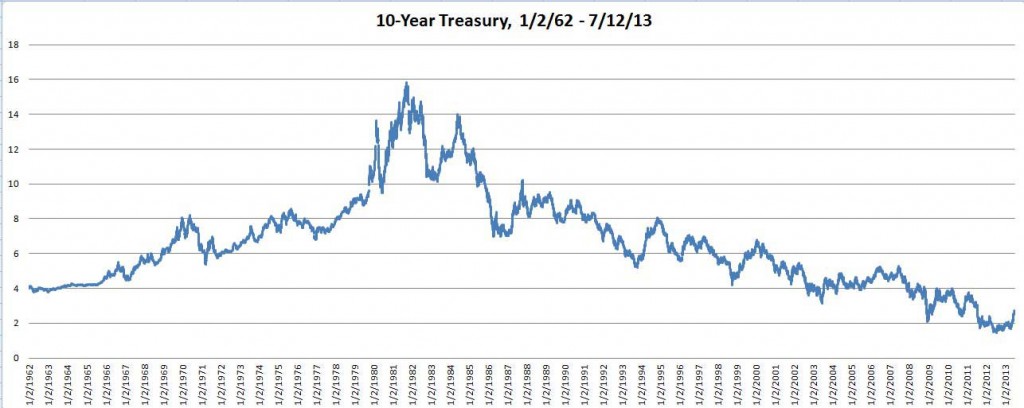

You can read that post for all the details but the conclusion is that government debt has gone critical. Massive interest required to service such a massive debt load. Increasing bond yields. Increased government expenditures. Government debt will continue its alarming upward trajectory at an ever accelerating pace.

Inflation Versus Deflation

At last we have all the pieces to attempt to answer the question we set out with: Will it be deflation or inflation.

My belief is that, while the deflationists may at first appear to be correct, in the end inflation must win.

It comes down to two opposing forces at work:

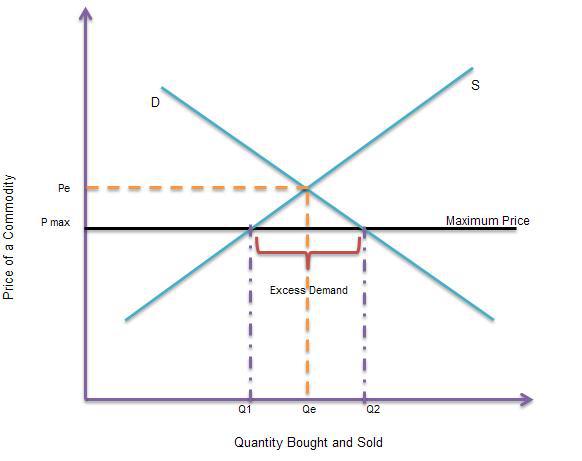

- Deflationary pressure from economic downturn causing tightening credit markets and decreasing velocity of money.

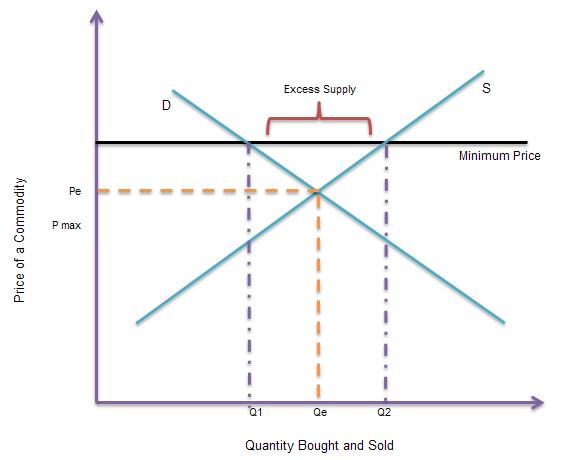

- Inflationary pressure from debt monetization and QE.

The key is that the acceleration of these two pressures is fundamentally different.

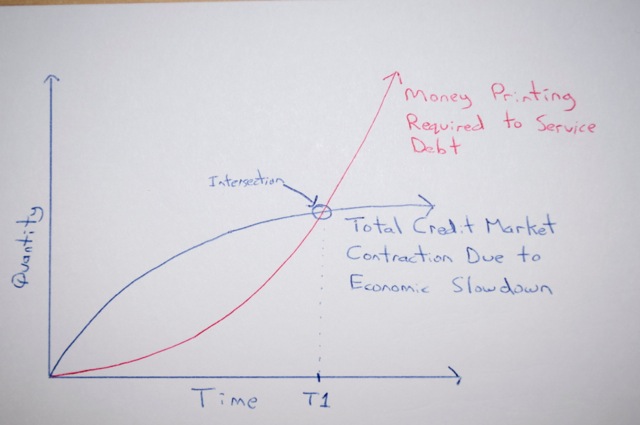

There is a lower bound to the deflationary pressured resulting from the decrease in the velocity of money. Once banks stop lending completely and credit markets freeze up, the deflationary impact of a decreasing velocity of money is exhausted. I would argue further that this deflationary impact initially has a large effect which diminishes over time i.e. the curve decelerates. The longer a crisis goes on, the less of an impact is made by tightening credit markets since those markets are already stressed. Regardless, even if the impact on money supply is linear, it is still bounded which is the key.

But the increase required to the money supply for debt monetization has quite a different characteristic. Clearly, as more and more debt exists, more and more money is required to service that debt. The curve grows at an accelerating rate. We can clearly see this already happening in the above chart of government debt.

It makes logical sense. The amount of money required to service ever growing debt goes to infinite. Money velocity can only slow to an absolute bottom of one which would represent a system with 100% bank capitalization and no fractional reserve. In the battle between printing and economic slowdown, printing wins.

Here’s how I visualize this tug of war:

At any point up to T1 (the point where the lines intersect), deflation can win out. After T1, inflation dominates.

Thus, I feel that, in the end, inflation is still the lion in the corner of the room. We are going to get mauled. The question is how close are we to the point of intersection. This I don’t know – and don’t believe anyone who claims to with certainty. The reality is we could still be earlier in the above graph in which case we may see a period of deflation. But, eventually we will cross the intersection point and enter a period of high inflation. You can’t print money without inflation.

Recovery Won’t Save Us

Even if the economy magically recovers prior to the intersection point (fat chance), that very recovery would cause money velocity to return to ‘normal’ levels i.e. increase. At that point all the money printing of the past would show up in the money supply as inflation. So even recovery is, at this point, a catalyst for inflation. There’s no way out here. Recovery or no recovery the beast of inflation bites sooner or later once you’ve fired up the printing presses.

Conclusion

We’ve unleashed the inflation monster. The collapsing economy has served to delay the inflationary impact of loose monetary policy. It will not continue to do this forever. At some point, recovery or not, we will have to pay the piper. Common sense, in this case the fact that printing money leads to inflation, wins.