If you’ve been following this series, so far I’ve covered:

- Part One. The timeline of events as they unfolded in Cyprus to the present day.

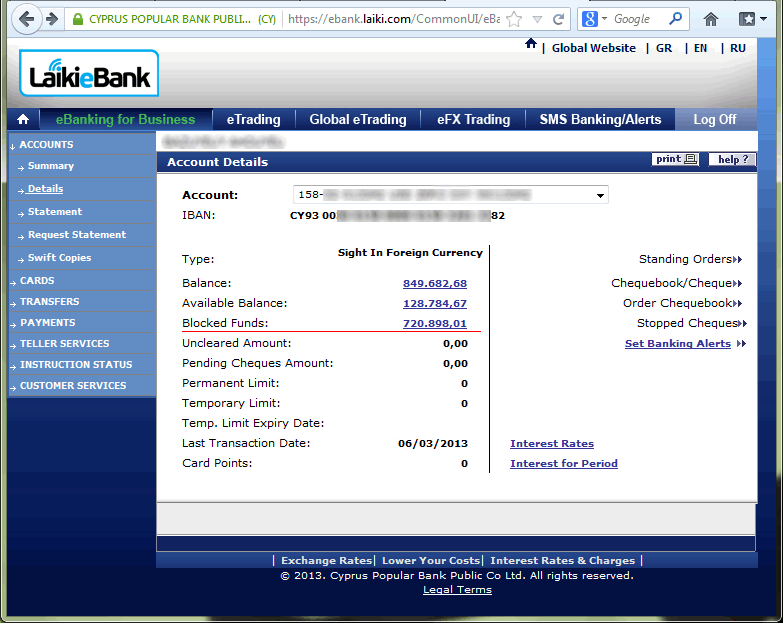

- Part Two. The impact on the Cypriot people and decimation of the small/medium business segment. This also looked at the corruption that got Cyprus into such a mess in the first place and the loopholes in the system that allowed the elites to withdraw their assets even as ordinary Cypriots were under oppressive capital controls.

- Part Three. The fact that bail-ins, as they occurred in Cyprus, will happen in other countries as the global financial crisis picks up steam.

In this final post of the series I want to focus on why Canadians should take the lessons of Cyprus to heart. The reality is that the 2013 Canadian budget specifically called out how the bail-in model will be used if any Canadian banks get into trouble.

So What’s in the 2013 Canadian Budget?

I have linked to the entire 2013 Canadian budget here but the section that is relevant for our discussion today can be found on pages 144 and 145 in the section titled ‘Establishing a Risk Management Framework for Domestically Systemically Important Banks‘. The entire section reads as follows:

Canada’s large banks are a source of strength for the Canadian economy. Our large banks have become increasingly successful in international markets, creating jobs at home.

The Government also recognizes the need to manage the risks associated with systemically important banks—those banks whose distress or failure could cause a disruption to the financial system and, in turn, negative impacts on the economy. This requires strong prudential oversight and a robust set of options for resolving these institutions without the use of taxpayer funds, in the unlikely event that one becomes non-viable.

The Government intends to implement a comprehensive risk management framework for Canada’s systemically important banks. This framework will be consistent with reforms in other countries and key international standards, such as the Financial Stability Board’s Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, and will work alongside the existing Canadian regulatory capital regime. The risk management framework will include the following elements:

- Systemically important banks will face a higher capital requirement, as determined by the Superintendent of Financial Institutions.

- The Government proposes to implement a ―bail-in regime for systemically important banks. This regime will be designed to ensure that, in the unlikely event that a systemically important bank depletes its capital, the bank can be recapitalized and returned to viability through the very rapid conversion of certain bank liabilities into regulatory capital. This will reduce risks for taxpayers. The Government will consult stakeholders on how best to implement a bail-in regime in Canada. Implementation timelines will allow for a smooth transition for affected institutions, investors and other market participants.

- Systemically important banks will continue to be subject to existing risk management requirements, including enhanced supervision and recovery and resolution plans.

This risk management framework will limit the unfair advantage that could be gained by Canada’s systemically important banks through the mistaken belief by investors and other market participants that these institutions are “too big to fail”.

To their credit, even the mainstream media reported on this with concern since, in bank parlance, deposits are considered liabilities. Thus, the statement ‘rapid conversion of certain bank liabilities into regulatory capital‘ certainly could imply deposits would be used as part of this recapitalization – exactly what we saw take place in Cyprus.

Move Along. Nothing to See Here

Immediately following this controversial section of the budget going viral, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s press secretary Kathleen Perchaluk issued the following statement to clarify:

The bail-in scenario described in the Budget has nothing to do with depositors’ accounts and they will in no way be used here. Those accounts will continue to remain insured through the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, as always.

The [Canadian] bail-in regime is to protect both taxpayers from having to bail out banks and depositors from having to take a financial hit like we’ve seen in Cyprus. If a bank is having severe difficulties, the bail-in regime would force certain debt instruments to be converted into equity to recapitalize the bank.

This clarification was immediately used to chastise all those who had reported with alarm on the language in the budget around the bail-in regime. The mainstream media was satisfied with this clarification and essentially reported in unison: False alarm, nothing to see here, move along.

A Clarification Not Worth the Paper It’s Not Written On

The first thing to point out is that it is the budget that is read before, and passed by, parliament. Once passed, these budgets form the basis for legislation. Conversely, random statements by MP’s press secretaries don’t in any way shape the laws that ultimately go onto the books. Such statements are, practically speaking, completely irrelevant.

That said, let’s analyze Kathleen Perchaluk’s statement. The thrust of her statement is: “Those accounts will continue to remain insured through the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, as always.“. Ok, two big problems with this:

- The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) is woefully underfunded (like all national deposit insurance schemes). In the event of a true crisis at one of the big six systemically important Canadian banks the CDIC is going to fold like a cheap lawn chair. This is a topic I’ll be exploring further in a future post.

- Only funds below $100,000 are insured by the CDIC. Thus, Kathleen’s statement does not in any way give comfort to those with accounts holding more than $100,000. Since those deposits are, by definition, uninsured, they are specifically excluded from Kathleen’s reassuring statement. This, to me, is more worrying than if no clarification had been made at all. Recall that in Cyprus it was an identical situation where only uninsured deposits over €100,000 got hit.

So, I must respectfully disagree with the conclusion of the mainstream media. Kathleen Perchaluk’s statement simply does not address the risk of a Cyprus-style confiscation of uninsured deposits at Canadian banks during a bank failure.

The Key to It All

So, the language in the budget is pretty concerning. It seems to specifically say that the same mechanism that occurred in Cyprus could be applied here. But where is this methodology of stealing deposits coming from? Why does it seem to be coordinated between countries?

The answer is in the above quoted section of the budget where it says:

This framework will be consistent with reforms in other countries and key international standards, such as the Financial Stability Board’s Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions…

It would seem that this document from the Financial Stability Board (FSB) is key to understanding the true intent of the language in the Canadian budget.

You can get the entire document for yourself here. I provide my analysis of the document below. I can’t begin to stress how important it is for Canadians to understand this. Adoption of this framework by the Canadian government guarantees that what happened in Cyprus will happen here in the event of a failure at one of our major banks.

What is the Financial Stability Board (FSB)?

So just what is the Financial Stability Board? You can hit their website here but essentially the FSB is an international working group of central bankers whose goal is to propose and promote methods for consistent regulation of the financial sector. Virtually every country’s central bank belongs to the FSB.

Canada is particularly well represented on the FSB with our Central Bank, Department and Finance and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions all being members. In addition, the outgoing Governor of the Bank of Canada, Mark Carney, has chaired the FSB since 2011.

What is the Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions?

This 2011 FSB document presents a framework for how to address failures at systemically important banks. This document has been ratified by all members of the G20 (including Canada) meaning that these countries all agree that the principals laid out in this document are the correct way of handling future bank failures. Canada has re-affirmed its commitment to abide by this framework by stating explicitly in the 2013 budget that this is the model it will use moving forward to deal with any banking crises.

Understand this FSB document and you understand Canada’s official policy on bank failures and whether Canadian depositors are at risk.

The document itself is very clearly laid out. There are over a dozen sections that specifically talk about imposing loses on unsecured creditors. Rather than iterate through these ad nauseam, let me simply show you the smoking gun that ties everything together:

Bail-in within resolution

3.5 Powers to carry out bail-in within resolution should enable resolution authorities to:

(i) write down in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims in liquidation (see Key Attribute 5.1) equity or other instruments of ownership of the firm, unsecured and uninsured creditor claims to the extent necessary to absorb the losses; and to

(ii) convert into equity or other instruments of ownership of the firm under resolution (or any successor in resolution or the parent company within the same jurisdiction), all or parts of unsecured and uninsured creditor claims in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims in liquidation;

I’m not sure how this could be any more clear. 3.5(i) clearly states that uninsured creditors (i.e. deposits not covered by CDIC) are to absorb losses. 3.5(ii) grants the ability to convert these same uninsured deposits into shares in the bank.

These two things are EXACTLY what happened in Cyrus. Uninsured deposits were made to absorb losses both directly and through conversion to worthless shares in the Bank of Cyprus.

Conclusion

People who insist that the Canadian budget does not sanction Cyprus style uninsured deposit confiscations are just plain wrong. Both the language in the budget and the referenced FSB document clearly indicate that bail-in by imposing losses on uninsured deposits is the preferred approach to resolving failures of systemically important banks.

And, the FSB’s document is not just some pie-in-the-sky proposal – the G20 has already agreed that this is the model to use moving forward. It clearly lays out the blueprint for exactly what happened in Cyprus. Cyprus wasn’t a one off – it was following the new global formula for dealing with bank failures. That same policy is now Canada’s model for resolving bank failures.

As the international crisis continues to unfold we now know exactly what to expect. If you have uninsured deposits in a Canadian bank those funds are at risk and will be confiscated in the event that bank fails. There is no gray area here. It isn’t a maybe. Your uninsured deposits will be made to absorb the losses in the event your bank fails.

Protect yourself. Get you money out and into hard assets or, at the very least, open accounts at separate financial institutions. CDIC will insure up to $100,000 per financial institution. So, while opening two accounts at RBC and putting $100,000 in each will result in only $100,000 insured, opening one RBC and one BMO account and putting $100,000 in each will result in the full $200,000 being insured.